What did Machen eat?

An old menu offers a glimpse of Machen's times

by Brad Isbell

One hundred years have passed since the publication of J. Gresham Machen’s classic polemic-apologetic book, Christianity and Liberalism. The world has changed a lot in the intervening century. The Protestant churches certainly look different, with the mainline (in and for which Machen fought) hurtling headlong into numerical and doctrinal oblivion. Evangelicals (who avoided liberalism and the Barthianism that followed) don’t look much better off in 2023 than do the Seven Rainbow Sisters of the mainline. Machen has been proven right about a lot of things. Thus, interest in him has been high in this centennial year of his great book.

There is still some mystery (and mystique) surrounding Machen. The mists of time cloud our view of him. We do have a number of images of him (mostly dour portraits), so we have a good idea of his appearance throughout his 55 years of spiritual struggle and ecclesial combat. Though Machen was an early adopter of radio1 as a Christian teaching medium, no recordings of his voice have been found. We do not know what he sounded like. Questions remain: Did he retain the segregationist views he privately espoused 20 or more years before his death? Why did he never marry? Did he have a girlfriend at one time? As questions of sex and race have intensified in the culture, activists and axe-grinders have not always been charitable or fair when assessing these aspects of Machen’s life.

Machen did live in a different time. He also lived in a different class than most of us. He was sophisticated and well off, yet he lived simply—in a dorm at Princeton and then, from 1929, in an apartment in Philadelphia. But his suits were custom-made; his coats had special oversized pockets to keep books close at hand. Those of us interested in Machen welcome any help understanding his time and place; thus, an old menu from 1921 has set us thinking—what did (or would) Machen eat?

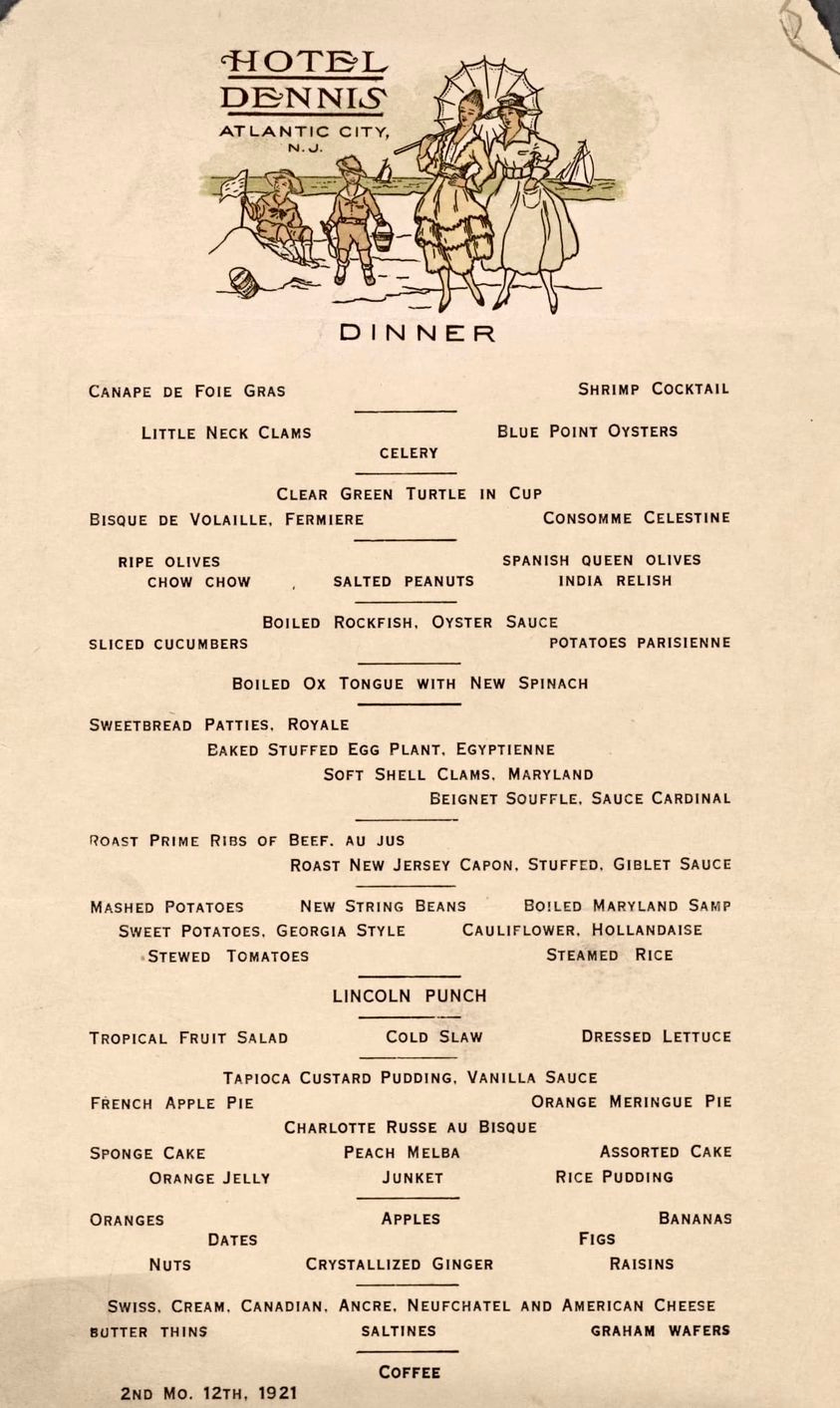

The menu2 in question is from a New Jersey hotel. Machen had to travel a lot, but also had the money to travel and stay in hotels just to have peace and quiet for writing and study, so he ate in many hotel dining rooms. The hotel in question is in Atlantic City, about 100 miles from Princeton and about half that distance from Philadelphia, his later abode. We have no reason to believe that Machen ate at this restaurant in 1921 while his great book was brewing, but we can’t say he didn’t eat there either.

Just as with the American religious landscape, so with menus: Much has changed, and much is familiar from one century to the next. This particular menu reads a bit like a map of Machen’s life and journeys. The first course reminds us of his early life and his formative time in France during the First World War.

Would Machen have been tempted by Canape de Foie Gras, Bisque de Volaille Fermiere, or Potatoes Parisienne? Very likely. He traveled in France in peacetime as well as while serving the war effort as a YMCA canteen operator who did battle with hot chocolate, rats, and supply chain issues rather than the Germans, though he did have to dodge a few shells and bugged out a time or two because of imminent danger. After the privations of war just a few years before, he probably enjoyed a bit of fancy French cuisine in 1921. As a Baltimore native, I think the clams, oysters, and shrimp might have been appealing as well. Machen’s very Southern mother was from Georgia, and he vacationed there as a youth. This suggests that the peanuts would have been irresistible, too. But “Clear Green Turtle (Soup) in Cup”…let’s hope not.

Now for the serious eating, the main course. The first item reminds us how much has changed. Would Machen salivate over the Boiled Ox Tongue with New Spinach? Somehow, we doubt it. Machen’s biographer, D.G. Hart, would surely weigh in here if he could. (Hart loves sweetbreads,3 so he would surely vote for the patties.) Few 21st-century Americans even know what sweetbreads are. For better or worse, here’s the scoop from Wikipedia:

“Sweetbread is a culinary name for the thymus or pancreas, typically from calf or lamb. Sweetbreads have a rich, slightly gamey flavor and a tender, succulent texture. They are often served as an appetizer or a main course and can be accompanied by a variety of sauces and side dishes.”

Mmmm, pancreas! But who are we to judge in the days of Big Macs and Big Gulps? Softshell clams from Maryland would surely take him back home, but—doughty fighter that he was—let’s vote for the prime beef rib. But look—more items from his ancestral homelands of Maryland and Georgia. It’s as if the menu was designed for him. Might Machen have sipped the Lincoln Punch, a rum-based cocktail? Maybe not. He was almost (but not quite) a teetotaler. We know only a bit of his beer drinking as a frat boy in Germany in the first decade of the 20th century. There is little evidence of him drinking later in life. Surely, in polite company, he sipped sherry or whatever was offered, but we’ll vote that he passed on the punch. Ironically, his failure to strenuously support Prohibition (on principle) was used against him by the political varlets in his New Jersey presbytery several years later. Mencken called a Machen a “wet” on the booze issue, but for all practical purposes, he seemed to have been quite “dry.”

“I have noted that Dr. Machen is a wet. This is somewhat remarkable in a Presbyterian, but certainly it is not illogical in a Fundamentalist. He is a wet, I take it, simply because the Yahweh of the Old Testament and the Jesus of the New are both wet—because the whole Bible, in fact, is wet. He not only refuses to expunge from the text anything that is plainly there; he also refuses to insert anything that is not there.” - H.L. Mencken, 1931

Remarkable that a presbyterian drinks? Have all the beardos-with-Scotch-and cigars memes been wrong? Yes, that’s another way things have changed in the last 100 years. The mainline liberals of the early 20th century were pietists and moralists of a sort…at least when the world was watching. And while we’re near the subject, we regret to inform you that Machen didn’t even smoke cigars. But he did approve:

“My idea of delight is a Princeton room full of fellows smoking. When I think what an aid tobacco is to friendship and Christian patience, I have sometimes regretted that I never began to smoke.” 4

The dessert/after-dinner section of this 1920s roars with carbohydrates—proof that they are no modern invention. Let’s assume that, being a biblical scholar, he was drawn to the figs and raisins, mentioned often in scripture. As a man of the Reformation, let’s hope he went for the Swiss cheese, though the Canadian cheese (whatever that is) might have appealed to him since he had climbed in the Canadian Rockies, though he preferred the Swiss Alps.

Doctrine matters, and we cannot escape from it, even when eating. Machen would have scorned one of these items—Graham Crackers, aka wafers.

Rev. Sylvester Graham, an assumedly New School Presbyterian in the northern church in the early 19th century, was (to put it delicately) NUTS. He was a moralizing temperance man who also turned to vegetarianism and thought his crackers would help men avoid certain sexual sins. Doctrine matters; crackers don’t! Machen loved the blessed freedom of the Gospel even as he lived a reserved life. He would have given Graham’s crackers the old stinkeye and ordered his coffee…strong and black.

UPDATE:

Researching the tragic last week of Southerner-at-heart Machen's life, an endearing detail emerges: He liked biscuits. Pastor Sam Allen, his host in Carson, ND, reported that the ill and declining Machen “could hardly touch a bite (at dinner), yet he never complained. He commended Mrs. Allen on her biscuits and said if he were himself he would pack away at least five.” This was on Dec. 29,. 1936, three days before he died. One assumes Machen's mother (from Georgia) introduced him to (and while she was alive, kept him in) biscuits.

This and many other classic menus are available here: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100064707491814

Stonehouse, J. Gresham Machen: A Biographical Memoir, 1987, p. 506.

It's finally happened...I can now mass produce my indispensable new religious accessory.

The WWME Bracelet. For such a time as this .