The liberalizing, equivocating mainliners of Machen’s day had not abandoned morality. Indeed, they hoped to use Christian morality to tame the savage immigrants and maintain city property values and quality of life. Machen here argues not for morality but for a much different thing: biblical holiness:

In the third place, the primitive Church was radically ethical. Religion in those days, save among the Jews, was by no means closely connected with goodness. But with such a non-ethical religion the primitive Christian Church would have nothing whatever to do. God, according to the primitive Christians, is holy; and in His presence no unclean thing can stand. Jesus Christ presented a life of perfect goodness upon earth; and only they can belong to Him who hunger and thirst after righteousness. Christians were, indeed, by no means perfect; they stood before God only in the merit of Christ their Saviour, not in their own merit; but they had been saved for holiness, and even in this life that holiness must begin to appear. A salvation which permitted a man to continue in sin was, according to the primitive Church, no matter what profession of faith it might make, nothing but a sham.

The holiness Machen was concerned for was ethical, but not merely ethical. It was not pragmatic morality that just made personal, economic, and political sense. It was not just best practices, but concerned the “weightier matters of the law." And Biblical holiness included attachment to the church and participation in her worship and work. All 10 commandments were still to be taught and obeyed—there was to be no toleration of loose living or loose churches.

These characteristics of primitive Christianity have never been completely lost in the long history of the Christian Church. They have, however, always had to be defended against foes within as well as without the Church. The conflicts began in apostolic days; and there is in the New Testament not a bit of comfort for the feeble notion that controversy in the Church is to be avoided, that a man can make his preaching positive without making it negative, that he can ever proclaim truth without attacking error. Another conflict arose in the second century, against Gnosticism, and still another when Augustine defended against Pelagius the Christian view of sin.

The respectable, for-the-culture-and-nation churches of Machen’s day were conflict-averse and ecumenism-attracted. Doctrine was thought to divide; feeling and experience and sentiment were thought to unite. The radically doctrinal and radically intolerant church Machen earlier described was simply the last thing Main Street Christians were looking for.

At the close of the Middle Ages, it looked as though at last the battle were lost—as though at last the Church had become merged with the world. When Luther went to Rome, a blatant paganism was there in control. But the Bible was rediscovered; the ninety-five theses were nailed up; Calvin’s Institutes was written; there was a counter-reformation in the Church of Rome; and the essential character of the Christian Church was preserved. The. Reformation, like primitive Christianity, was radically doctrinal, radically intolerant, and radically ethical. It preserved these characteristics in the face of opposition. It would not go a step with Erasmus, for example, in his indifferentism and his tolerance; it was founded squarely on the Bible, and it proclaimed, as providing the only way of salvation, the message that the Bible contains.

Machen was a Reformation man. He was not an Erasmus who downplayed distinctives. Nor was he an Erastus who wanted to give the state power over the church for the good of the church.1 One assumes that Machen had learned the lessons of history which many are ignoring today, namely that established or quasi-established churches never retain (or attain to) radical doctrinality (because precision is messy and inconvenient), radical intolerance (because unity must be maintained for the good of the nation), or radical ethical standards (because applying one standard to peasant, parliament, poobah, and prince never quite seems to work out). The Christian Nationalism we hear about today is arguably a rerun of the bland, misguided, nation-serving ecumenism that radicalized Machen in 1920.

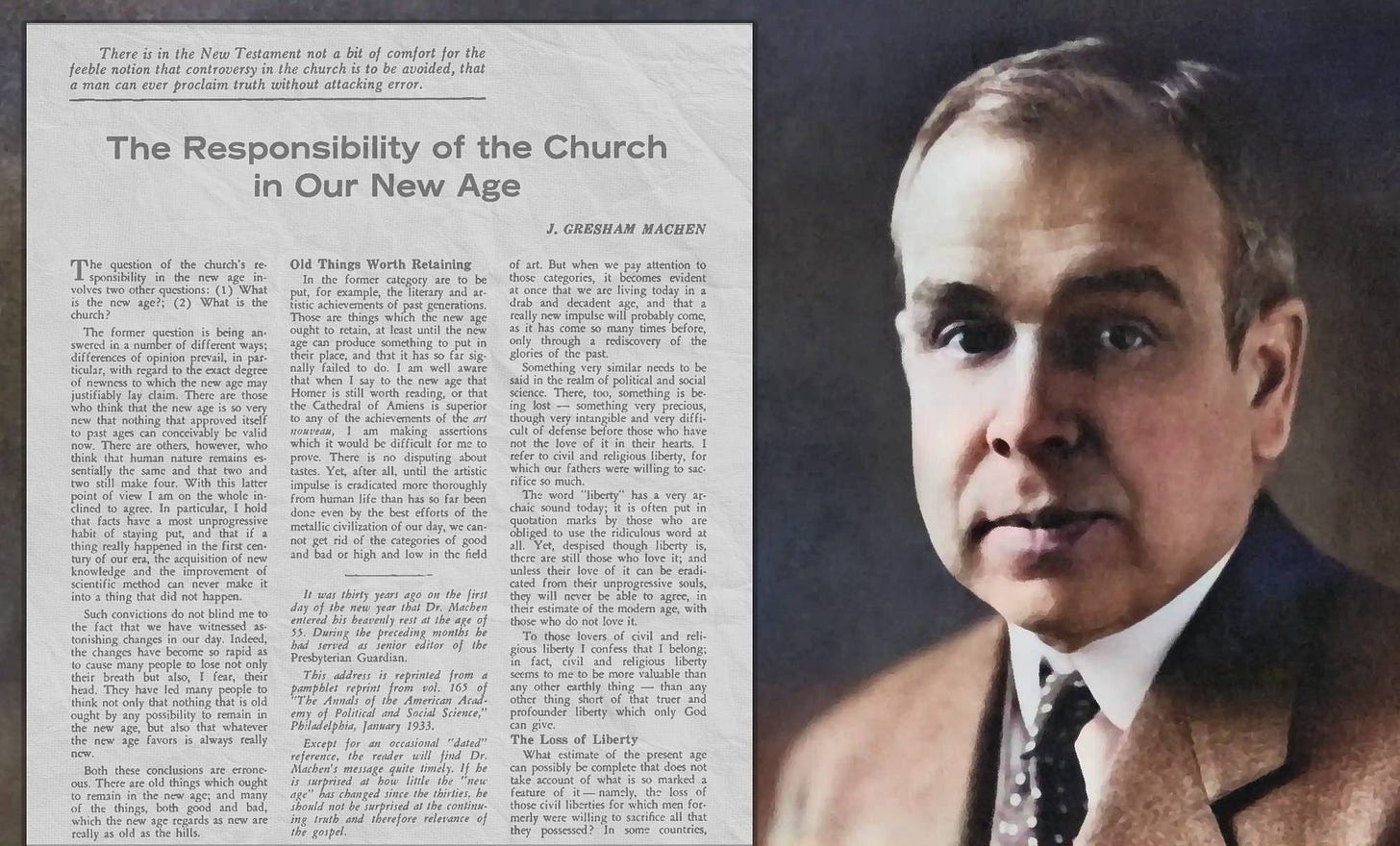

Read The Responsibility of the Church in Our New Age in full.

Listen to a fine reading of the article (39 minutes) by Bob Tarullo.

Stay tuned for future installments - by Brad Isbell

READ PART 7

Some Christian nationalists today say that the church should not be dominated by the state, but still would give a “prince” power to approve councils, build churches, pay pastors, and punish bad ministers. A preferred, paid, and propped-up church will always serve its earthly master.