Machen vs. Women - A War He Never Fought

A Nicotine Theological Journal original, updated again in 2025

by Brad Isbell

J. Gresham Machen ministered in a denomination, the Presbyterian Church (USA), which had female deacons in the fold or on the boards by the time he became an active elder. That fact set me to thinking.

The essay below was originally published in the Nicotine Theological Journal in January of 2022. While preparing for a podcast interview, I did a bit more research and found that the status of female deacons and deaconesses in the PCUSA in the 1920s was more complicated than I knew. I also learned that every book of church order has its vagaries and deficiencies.

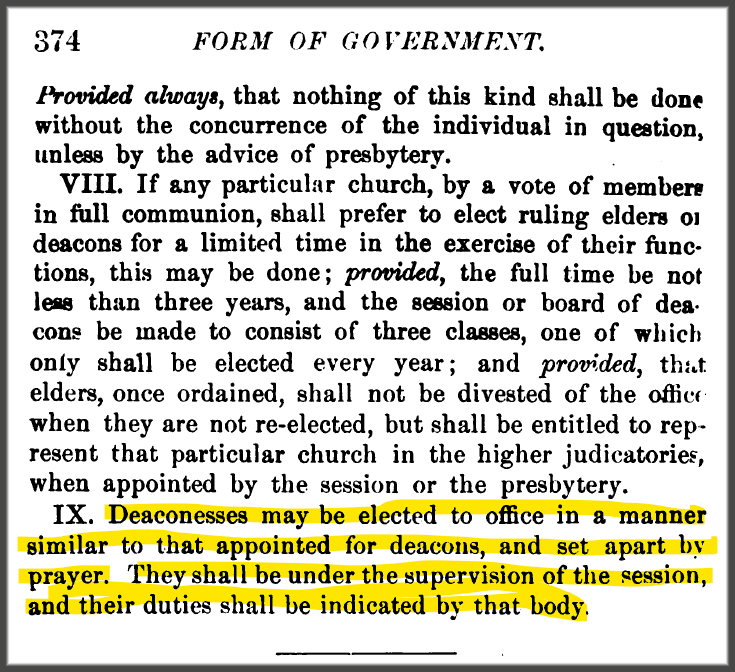

Ordained female deacons in the Northern church resulted mainly from the receiving into the PCUSA in 1905-1906 the greater part of the old born-in-revival Cumberland Presbyterian Church, which already had female deacons. Sometime between 1905 or 1906 and 1922, the PCUSA went from having informal deaconesses or inherited (grandmothered in?) Cumberland lady deacons to the real, official thing. Here’s the first mention of official lady deacons in a copy of the PCUSA constitution to which we have access (1922):

Section II is not a triumph of the English language. (By comparison, the PCA Book of Church Order is much more expansive and precise in terms of offices and the qualifications of officers.) To make things even less clear, we have a stray reference to deaconesses a page or two later:

It’s not entirely clear whether this refers to a more informal, unordained, locally variable quasi-office or to the fairly new office of female deacon. Maybe it’s the former…a thing that had been around for a while. If so, the PCUSA of the 1920s was much like the PCA of the 2020s, which seems to have a de facto “office” of deaconess or female deacon, though unordained.1 The PCUSA constitution was frustratingly short on definitions. Deacons (whether of the XY or XX type) seem not to have been a big deal in the Northern church. They were not for Machen…as far as we know. I considered why this might be for the NTJ:

Machen vs. Women - A War He Never Fought

To anyone familiar with J. Gresham Machen’s biography the words, “Machen and women” will bring two facts to mind: that Machen never married and that he had a particularly intimate relationship with his mother. Much of what we know about Machen comes from the voluminous trove of letters to his mother. His views on segregation (shared in an early letter or two) have gotten him in particular trouble in the era of Wokeness. And in the era of Revoice there is new, if unfounded, speculation about his bachelorhood. And there is ongoing disagreement about the nature of his one (and only?) alleged romance with a Unitarian lady.

The more ecclesial-minded Machenite might well have another question: Where did Machen stand on the issues of women, office, and ordination in presbyterian churches, particularly his own? I, at least, have thought a lot about this murky issue. No biographers have cited comments from Machen on these issues, and if such comments existed, they would loom large in women’s ordination debates that bubble up from time to time in conservative Presbyterian and Reformed churches. Some consider women’s ordination a sort of canary in the confessional presbyterian coal mine: any talk of approving it being viewed as an indicator of faltering biblical fidelity or as symptoms of cultural compromise.

History may be our only helper in discerning Machen’s views, so here’s some history. The northern Presbyterian Church in the USA (in which Machen labored until 1936) first ordained women as deacons, serving equally with men, in 1923, though there may have been a less-formal deaconess role previously allowed or maintained, somewhat like many PCA churches have today. Machen’s opinion on admitting women to the ordained officeriate is unknown. Maybe he was indifferent. Maybe he shared the views of his Princeton colleague, the great B.B. Warfield, who favored some sort of “deaconing women,” to use a Tim Keller term.2

More likely, the issue was just not on Machen’s radar...he was busy battling theological liberalism (which he called “a different religion from Christianity”) in his Christian church. He described liberalism this way in his landmark book Christianity and Liberalism which was published the same year (1923) that pious PCUSA elders first laid hands on deaconing women. Machen was fighting for the life of his denomination in the 1920s, so it just may be that “little” things like deacons in skirts seemed insignificant compared to atrocities such as the Auburn Affirmation, which undermined nearly all the essential doctrines of the church.By 1930 when women ruling elders were first ordained, Machen was fighting for his own ecclesial life, having become persona non grata with PCUSA elites, and was fighting for the life of his newly-established seminary, having resigned from Princeton after nearly 25 years of association with the northern church’s flagship theological school.

Machen was a busy man. Maybe he never married for that reason alone. He may also have lacked the time or energy to address the women-as-officers issue. We'll never know.

When it comes to women in church office, the views of Robert Speer are not unknown. Speer was an esteemed, broad-church evangelical, a PCUSA missions major-domo, and one of Machen’s archnemeses. Speer, along with Princeton figures Charles Erdman and J. Ross Stevenson, represented the sort of peace-loving pious moderate that ultimately doomed the PCUSA to a slide into unbelief. He was a major supporter of the 1928 commission3 of fifteen elite women (Speer’s wife among them) who met in Chicago. Their work, cheered and guided by Speer, led to three overtures, but Speer did not get all he wanted in 1930. The two proposals to de-sex the PCUSA book of church order entirely or allow women to serve in preaching roles failed. The one to allow female ruling elders passed.

Again, Machen’s view of these issues is unknown. His friend Clarence Macartney was an outspoken but unsuccessful opponent of the changes. By this time Machen would have been loath to favor anything Speer supported, but…silence. Was it single-minded devotion to the most pressing issues or indifference that kept Machen from fighting these ecclesial innovations? Many conservative critics say that the great failure of Machen and his allies was the fact they did not file more ecclesial charges. Rather, they simply argued, tried to persuade, and sought to win assembly votes and hold positions of influence. Maybe they should have been more concerned with “broken windows policing” of polity issues— issues which may have seemed small then, but seem huge today.Whether the ordination of women to the offices of deacon, then ruling elder was inevitable and just a symptom of the slide or whether it actually made the slope all the more slippery…well, that’s a subject of debate. Women pastors in the PCUSA did not gain approval until 1956, two decades after Machen’s untimely death. It seems that it took so long for women to climb into pulpits, considering the movement for full women’s equality began in 1930.

One strong piece of evidence for Machen’s opposition to women officers remains: The denomination he fathered in 1936, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, restricted all of its offices—deacon, elder, and pastor—to men from the very beginning.Presbyterians of the 21st century will need Machen's stubbornness and high-minded commitment to doctrine to withstand the coming intersectional-egalitarian onslaught. And they may need an even more robust commitment to biblical polity than the men of Machen’s day—even the Bible-believing conservatives—were able to muster.

The ordination of female deacons is not automatically a slide into liberalism. A biblical argument can be made for them, and at least one very conservative Presbyterian denomination (the RPCNA) has had female deacons for a hundred years. The question should be discussed based on its biblical merit, not on its assumed "beginning of the end" reasoning. However, the informal allowance of something that is formally disallowed is helpful to no one!