What Is the Church?

Working through a landmark Machen article, part 5

…if the real trouble with the world lies in the soul of man, we may perhaps turn for help to an agency which is generally thought to have the soul of man as its special province. I mean the Christian Church. That brings us to our second question: What is the Church?

Again, there is nothing new under the sun. There is “trouble with the world” in 1933 and it would soon grow to unimaginable proportions. Surely Machen (who saw with more clarity than many what was coming) should have proposed a political or material solution. He was, after all, writing in a journal of political and social science whose readers assumedly believed in political and social solutions. But no, Machen had something else in mind: “an agency which is generally thought to have the soul of man as its special province.” Why did he refer to the church in this way? Probably because the doctrine of the spiritual and special mission of the church was being derided or abandoned. The church was considered a general cure-all for society’s ills…practically a quasi-government organization (an NGO?) serving material and national needs. Its mission was temporal inasmuch as it needed to constantly adapt to modern exigencies. The visible church must be seen to be doing something about all the things.

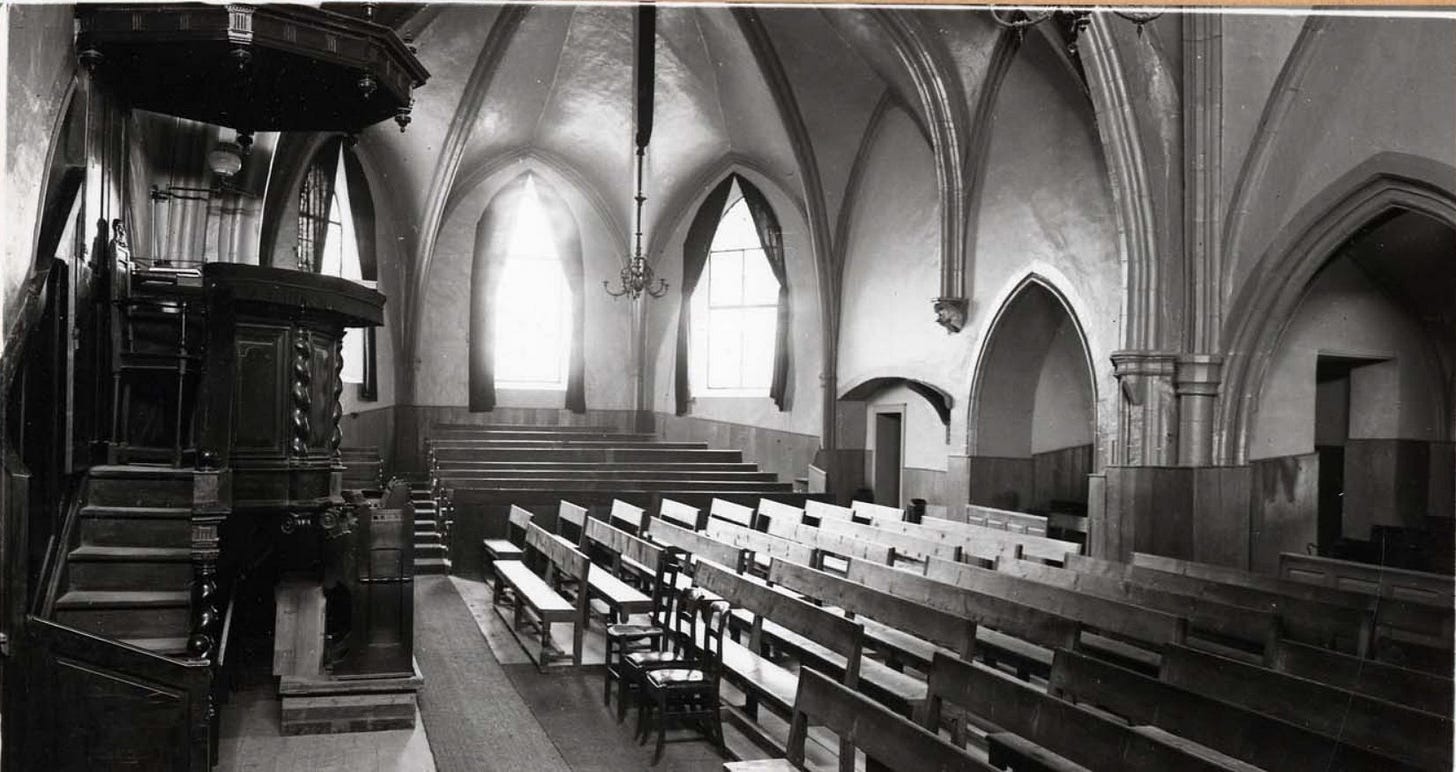

The question of what the church is and what its mission is to be cannot be separated. Chapter 25 of the Westminster Confession is helpful:

2 .The visible church, which is also catholic or universal under the gospel (not confined to one nation, as before under the law), consists of all those throughout the world that profess the true religion; and of their children: and is the kingdom of the Lord Jesus Christ, the house and family of God, out of which there is no ordinary possibility of salvation.

3. Unto this catholic visible church Christ hath given the ministry, oracles, and ordinances of God, for the gathering and perfecting of the saints, in this life, to the end of the world: and doth, by his own presence and Spirit, according to his promise, make them effectual thereunto.

The visible church’s mission is spiritual. It is a house for a family. It is about the salvation—by grace through faith—of sinners. The means by which this gracious salvation is accomplished are word and sacrament. The persevering members of this family do things in the world, preserved and perfected by Christ’s (spiritual) presence and the work of the Holy Spirit according to covenant promises which no longer concern only one nation or people. The telos for the church is not an improved world with less poverty, ignorance, and war, but the gathering and perfecting of a multitude without number who will—in time and for eternity—worship the Triune God in spirit and truth. This was probably not what the social and political “scientists” wanted to hear.

But maybe some political, practical program could be derived from the church’s history:

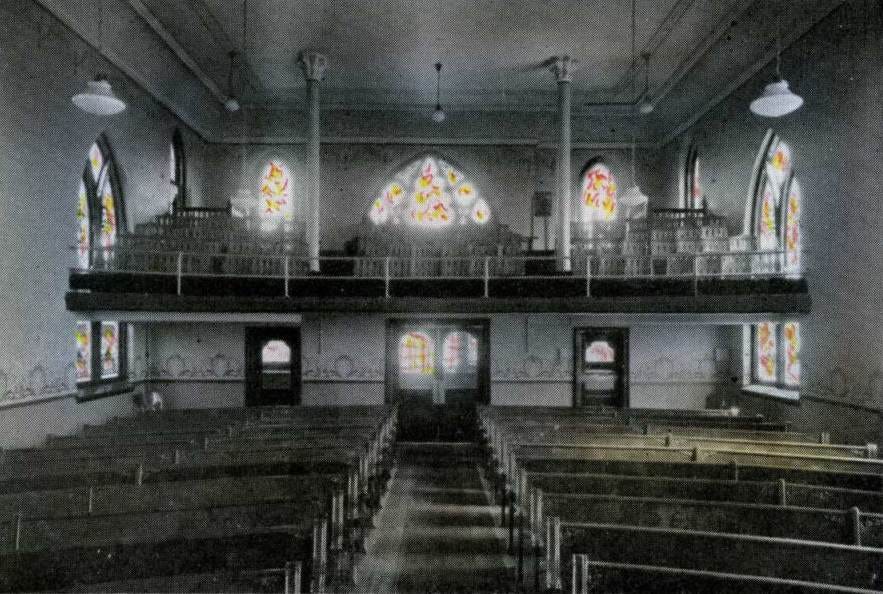

About nineteen hundred years ago, there came forth from Palestine a remarkable movement. At first it was obscure; but within a generation it was firmly planted in the great cities of the Roman Empire, and within three centuries it had conquered the Empire itself. It has since then gone forth to the ends of the earth. That movement is called the Christian Church.

What was it like in the all-important initial period, when the impulse which gave rise to it was fresh and pure? With regard to the answer to that question, there may be a certain amount of agreement among all serious historians, whether they are themselves Christians or not. Certain characteristics of the Christian Church at the beginning stand out clear in the eyes both of friends and of foes.

An empire conquered! Now Machen has our attention, but the politicos will be disappointed; the sociologists will find no new program proposals.

It may clearly be observed, for example, that the Christian Church at the beginning was radically doctrinal. Doctrine was not the mere expression of Christian life, as it is in the pragmatist skepticism of the present day, but—just the other way around—the doctrine, logically though not temporally, came first and the life afterward. The life was founded upon the message, and not the message upon the life.

“Do this and live” would always fail. The church’s program (whether ascendant or embattled, majority or minority) is “Believe this and live.”

The “this” is doctrine—truth preached and taught…news that was not fake. Machen wrote something very similar 10 years earlier in Christianity and Liberalism:

About the early stages of this movement definite historical information has been preserved in the Epistles of Paul, which are regarded by all serious historians as genuine products of the first Christian generation. The writer of the Epistles had been in direct communication with those intimate friends of Jesus who had begun the Christian movement in Jerusalem, and in the Epistles he makes it abundantly plain what the fundamental character of the movement was. But if any one fact is clear, on the basis of this evidence, it is that the Christian movement at its inception was not just a way of life in the modern sense, but a way of life founded upon a message. It was based, not upon mere feeling, not upon a mere program of work, but upon an account of facts. In other words it was based upon doctrine. (C&L, ch. 1)

The Christian life was important, but it did not come first. The “life” might or might not conquer an empire or a city (and only imperfectly and temporarily at that). Outward conformity to a “cultural Christianity” was not enough; the side effects were not the raison d'être:

But how was the life produced? It might conceivably have been produced by exhortation. That method had often been tried in the ancient world; in the Hellenistic age there were many wandering preachers who told men how they ought to live. But such exhortation proved to be powerless. Although the ideals of the Cynic and Stoic preachers were high, these preachers never succeeded transforming society. The strange thing about Christianity was that it adopted an entirely different method. It transformed the lives of men not by appealing to the human will, but by telling a story; not by exhortation, but by the narration of an event. It is no wonder that such a method seemed strange. Could anything be more impractical than the attempt to influence conduct by rehearsing events concerning the death of a religious teacher? That is what Paul called "the foolishness of the message." It seemed foolish to the ancient world, and it seems foolish to liberal preachers today. But the strange thing is that it works. The effects of it appear even in this world. Where the most eloquent exhortation fails, the simple story of an event succeeds; the lives of men are transformed by a piece of news…Nothing in the world can take the place of truth. (C&L, ch. 1)

Machen never got over this. And he never catered to those who saw the church as a mere “faith-based organization” (remember the 2000s?) for temporal good.

Read The Responsibility of the Church in Our New Age in full.

Listen to a fine reading of the article (39 minutes) by Bob Tarullo.

Stay tuned for future installments - by Brad Isbell

READ PART 4