Wars, rumors of wars, and instant news: Nothing new under the sun!

For a few minutes in 1972 I thought the US had been invaded...by the British.

By Brad Isbell

The year was 1972, the month was July, and I was living the summer school’s-out vacation dream in the small town of Senath, Missouri that I’ve often compared to Andy Griffith’s Mayberry. How was it like Mayberry? Well, I could walk two blocks from home on an actual sidewalk and be at the four-way stop of the tiny downtown. It had a flashing red light—not an actual traffic light—and it was almost always watched over by a volunteer sheriff’s deputy whose four-door Ford Maverick sedan (in brown or pale green, as I recall) was festooned with all manner of antennae. My dad pronounced it the most well-guarded intersection in the country. He usually found the humor in any setting or situation.

Walking a block or two in any direction from the intersection would take me to the grocery store, bank, library, fire station, city hall, First Baptist Church, a furniture store owned by one of our deacons (whose wife was my first grade teacher), the post office, and a gas station owned by my dad’s best friend—a real-life Wally’s filling station that would patch the inner tubes of my bike tires. Oh, and there was a barbershop with a shoeshine boy called Kokomo who was actually middle-aged and a bit “slow.”

I was seven, and like every kid in the US in the 1970s, I had a “banana bike” with obnoxious curved handlebars. It was not a fancy Schwinn but a humble Murray or Huffy. It was built to be accessorized; it variously sported a basket, noisemakers, a bright orange flag on a fiberglass rod for safety(?), and—best of all—a combination AM radio, electronic horn, and flashing light that clamped onto the handlebars.

It was from this radio while riding down Commercial Street that I thought I received disturbing news: “The British Army has invaded Northern Iowa.” Why (besides being seven) was I inclined to believe such a thing? There was no 24-hour cable news cycle, no Twitter/X or Alex Jones, but network radio brought staticky tweet-length news bulletins quickly. And 1972 was a rough year in world events, society, and politics. Already that year I would have heard about revolutions and coups, a number of acts of terrorism, the seemingly endless Vietnam war (complete with nightly body counts on the TV news), plane crashes, and tumultuous Washington politics (Nixon) and protests. Bad news of war, strife, and turmoil was entirely believable. Of course, I had misheard.

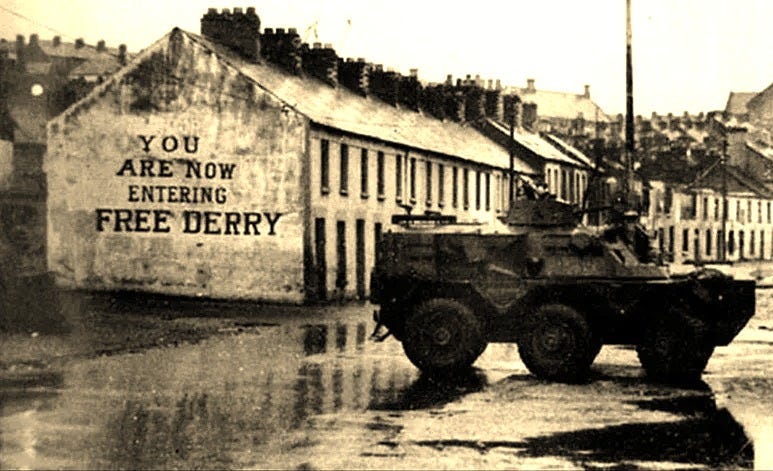

What the scratchy radio broadcast reported on Monday, July 31 was Operation Motorman, which retook "no-go areas" controlled by Irish republican paramilitaries in Belfast and other urban areas of Ulster—Northern IRELAND, not Northern Iowa. “The Troubles” were all over the news in the 70s and they reminded us that even the English-speaking world had not moved beyond civil war and political violence.

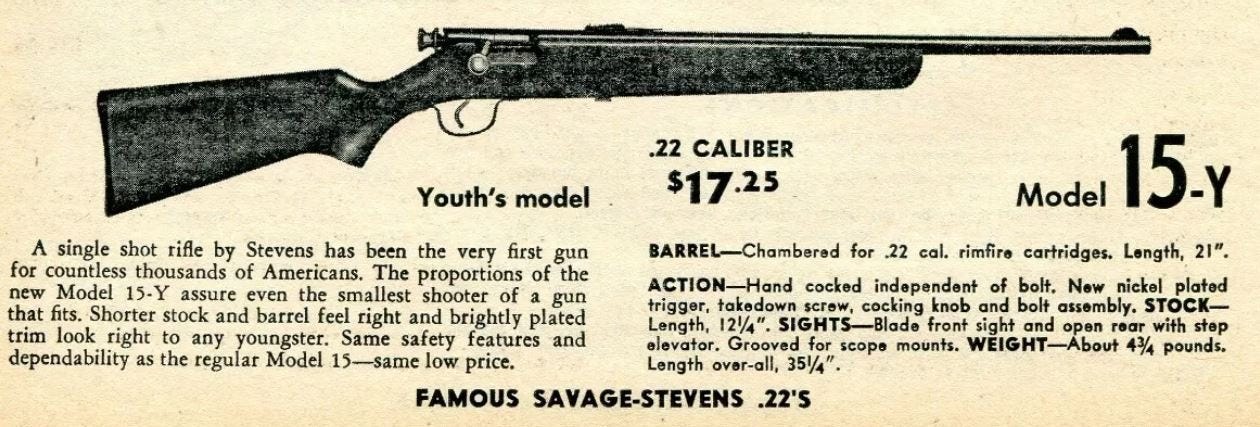

I was a junior military buff. I had read (or was reading) at this time nearly everything our small local library had on World War II and the War Between the States. I still remember the skeptical looks the librarian, Mrs. Jessie Fern Buck, gave me when I checked out stacks of adult war history books, which I did read. The ongoing Vietnam War, though, was less than inspiring. I was looking for a better war and taking up arms against the Bloody British only 600 hundred miles away was an exciting prospect. My dad, after all, had a single-shot Stevens .22 rifle, the barrel of which I had often dreamed of attaching to my bicycle handlebars—a thing which, had I done, would have required the removal of my radio and thus would have prevented the drama of the day in question). But I digress.

I rushed home and excitedly reported this news to my mom. She set me straight pretty quickly. My romantic plans for patriotic valor were dashed on the rocks of reality.

A little research shows that the 1970s were no less troubled than our own day, but I don’t remember a lot of drama or angst at home. My parents didn’t shield me from these events, but talked about them calmly. Most of what I remember about Vietnam was my mom and other church ladies putting together care packages to send to soldiers and watching home movies sent from the son of my dad’s gas station-owning friend, who served on the deck of an aircraft carrier off the coast of Vietnam. The takeoffs and landings were thrilling. The son had reported that the pilots were given “a can of Budweiser” between sorties while their planes were refueled and rearmed. Even though I was a good little Southern Baptist boy, this struck me as altogether reasonable.

The Cold War was an ever-present reality, too. Our town in the Bootheel of Missouri was barely 15 miles as the crow flies from the Strategic Air Command base in Blytheville, Arkansas, home of a B-52 bomber wing. I knew what those bombers carried and why. The base strongly resembled the one seen in Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1961 movie Dr. Strangelove. I could look up in the sky at almost any hour of the day or night and see B-52s or the tankers that served them. It was impossible to forget that “nuclear combat toe to toe with the Rooskies” (to quote the movie) was always possible.

Still, I don’t remember a lot of angst. Maybe America was just more optimistic then. Maybe the news cycles and sources were more humane. Or maybe my Christian parents did a good and wise job of dealing with the events of their day and how they talked about them, remaining calm and being realistic. Maybe we should try to do the same. Remembering that our times aren’t really that unique might be a good first step in that direction.

One final reminiscence: Though our Mayberry in the Delta seemed crime- and strife-free, it really wasn’t. A few months after we moved away from there to Arkansas, one of the barbers from that Main Street shop shot a man down outside the gas station where I often hung out and killed time. There truly is nothing new under the sun.