Newspaperman H.L. Mencken was something like the Christopher Hitchens of his day. His savage skepticism routinely roasted religious types, but he retained a special respect for fellow Baltimore native J. Gresham Machen. We’ll work through Mencken’s 1931 editorial for The American Mercury:1

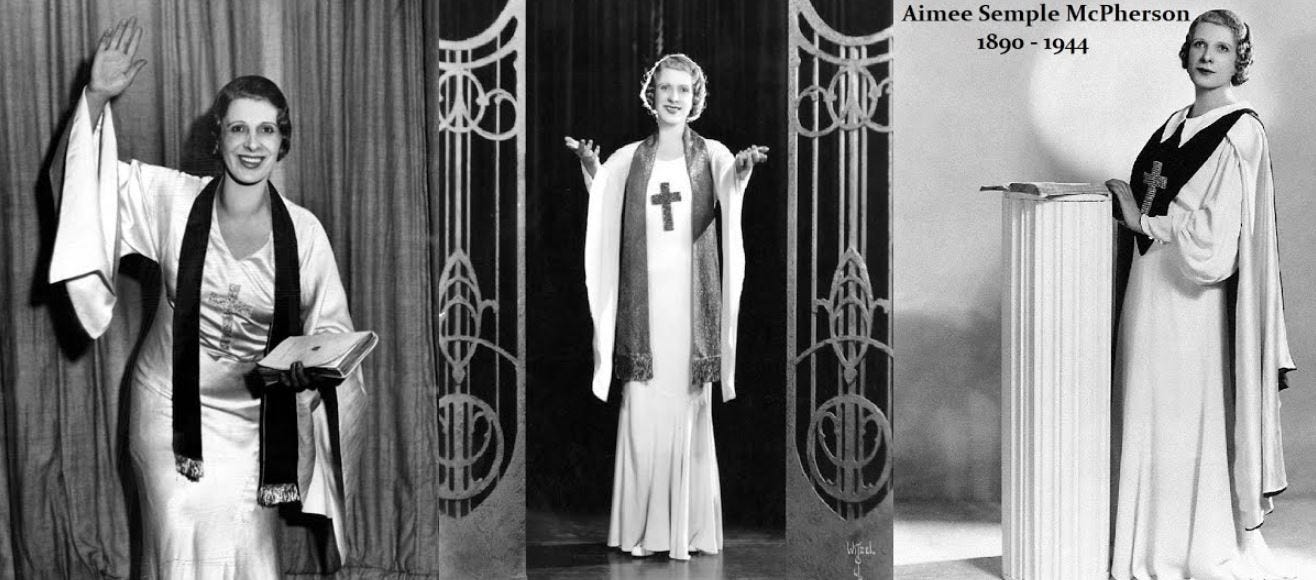

Thinking of the theological doctrine called Fundamentalism, one is apt to think at once of the Rev. Aimee Semple McPherson, the Rev. Dr. Billy Sunday and the late Dr. John Roach Straton.

McPherson was the bizarre pentecostal prophetess whose “ministry” and celebrity prophesied the hucksters, faith healers, and tacky televangelists to come later in the century. To our knowledge, Machen never commented on her at all. Sunday was the well-known revivalist about whom Machen was guardedly favorable: “Every morning, on the page of the paper devoted to Billy Sunday, a Unitarian statement appears in opposition. I like Billy Sunday for the enemies he has.” Straton was a political, moral crusading, anti-evolutionist baptist. Machen differed greatly from this low-brow trio, which would be Mencken’s point.

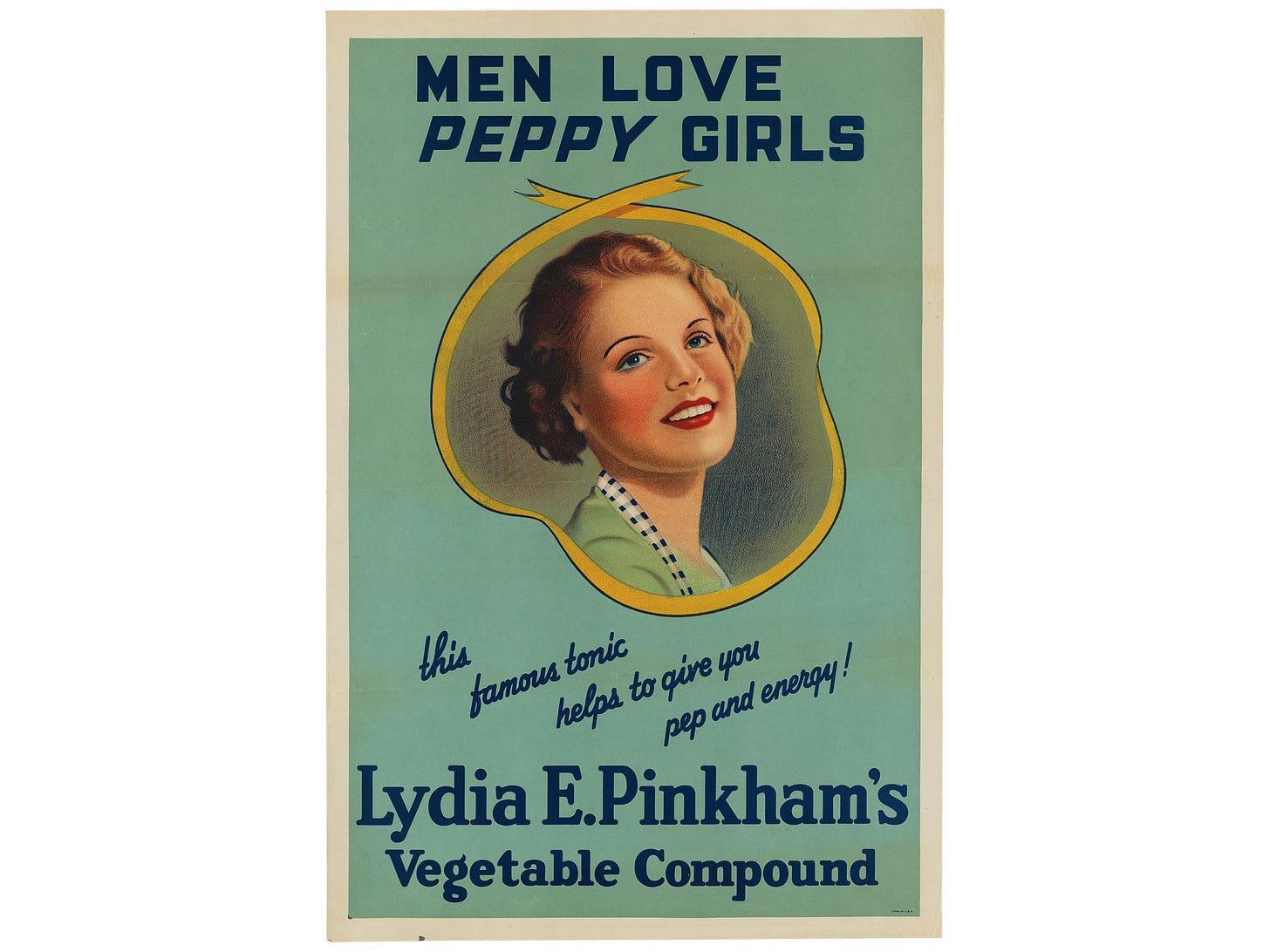

It is almost as if, in thinking of physic, one thought of Lydia Pinkham or Dr. Munyon. Such clowns, of course, are high in human interest, and their sincerity need not be impugned, but one must remember always that they do not represent fairly the body of ideas they presume to voice, and that those ideas have much better spokesmen.

“Physic” meant medical treatment, usually with medicine. Pinkham and Munson had popular eponymous patent medicines (made up largely of alcohol)—they sold snake oil and played on the gullible. Mencken contrasted the quacks to Machen, sometimes called a “highbrow” fundamentalist:

I point, for example, to the Rev. J. Gresham Machen, D.D. Litt.D., formerly of Princeton and now professor of the New Testament in Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia. Dr. Machen is surely no mere soap-boxer of God, alarming bucolic sinners for a percentage of the plate. On the contrary, he is a man of great learning and dignity—a former student at European universities, the author of various valuable books, including a Greek grammar, and a member of several societies of savants.

That Mencken was aware of Machen (whom he never met) speaks to the extensive newspaper coverage given to religious controversy in the early 20th century. Machen must have chuckled at “societies of savants.” The Reformed savants you will always have with you. Mencken now evokes the political-religious issues of 100 years ago:

Moreover, he is a Democrat and a wet, and may be presumed to have voted for Al in 1928. Nevertheless, this Dr. Machen believes completely in the inspired integrity of Holy Writ, and when it was questioned at Princeton he withdrew indignantly from those hallowed shades, leaving Dr. Paul Elmer More to hold the bag.

Machen was, in fact, a Democrat.

A “wet” was someone who opposed Prohibition. In Machen's case, this was because of principle, not because he was a big drinker. He was more or less a teetotaler post-German student days, where he may have drunk beer. Beer, in Germany—who can imagine such a thing?2

“Al” was Al Smith of New York, the 1928 Democratic Party presidential candidate who lost in a landslide to Herbert Hoover. Smith would have been the first Roman Catholic president and was noted for his opposition to the Ku Klux Klan.

Mencken was clearly aware of Machen’s troubles at Princeton.

Dr. More was a notable Christian apologist of his day. This shows all the more that Mencken understood Machen’s problems at Princeton, which began when he was nominated to hold the chair of apologetics at the denominational seminary—something the Great Men of the northern PCUSA could not abide.

More to come…

“The Impregnable Rock,” in The American Mercury 24, no. 4 (December 1931): 411-412 https://www.jstor.org/stable/26485518?seq=2

While a member of the rough equivalent of a German fraternity, he noted that his own group’s “temperance principle seems to be essentially that nobody is compelled to drink more beer than he chooses.” It is hard for me to believe that the Machen family didn’t sip sherry at Christmas or wine with grand meals.